Objeto não identificado

"I MISS MY PRE-INTERNET BRAIN", said a 2021 poster in uppercase as part of a series of works by Canadian artist, researcher and author Douglas Coupland. "I miss my pre-Internet brain" still seems, even ten years later, to resonate as a relevant allegory of contemporary life, since we go through, individually and collectively, a brutal process of reformulation of our brains.

As the world begins to be transformed into an avalanche of information 24/7, we have experienced vertigo: we are unable to process such an amount of stimuli. As a result, we see ourselves in a dual situation, immersed in hyperactivity, connected yet simultaneously struck by passivity, as if our psychic and cognitive channels were overloaded, blocking our ability to deal with the challenges of the present and their complexities.

Duality continues when we notice the excessive sharpness surrounding how we handle the most trivial aspects of everyday life. Information, screens, networks are addressed at all times at their full hyper-sharp spectrum. In order for the flow not to be interrupted, opacity and questions are not welcome. However, this same regime of transparency does not make us perceive the world more or better. On the contrary, it is related to a certain dullness of the eye and to some sort of shuffling of our cognitive abilities.

If this ultra-definition state of a world saturated with stimuli of all sorts has led to an atrophy of the senses and a flattening of multiple experiences, how can we cultivate a territory for objects that are still unidentified? How can we affirm the relevance of opacity, interruption and strangeness, in lieu of transparency, automatism, and familiarity? These are some speculations suggested by the works gathered in this exhibition.

We live in a time in which we distance ourselves from the perceived reality, to the extent that we spend a considerable part of our time in digital zones whose screens–always smooth and clean–simulate a non-human temporality for which the marks of time, imperfections, would never arrive. This time, permeated by canvases and marked by the dilution of the bodily dimension of the relationship with the world, is evoked in different works of this exhibition. "Command Prompt" (2019), by Vitória Cribb, shows a tortuous amalgamation between language, body, and machine. Cribb's work finds echo in a work dated forty years earlier. In Sonia Andrade's "Untitled" (1977), we hear the artist's voice repeat the phrase "turn off the TV” 196 times, like a mantra. Andrade's video, a pioneer of video art in Brazil, relate body and image while questioning the TV’s ability to "seduce, inform, distort, and manipulate".

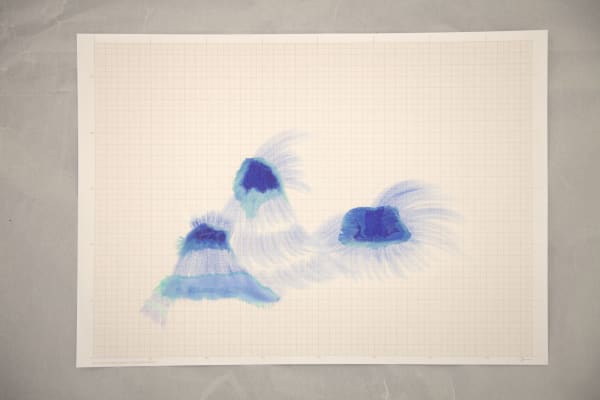

With caustic their approaches, Gustavo Torres and Marilá Dardot present allusions to different situations caused by virtual interaction. In Torres' video, we see different people sleeping in front of the camera. The scenes come from chats in which users unintentionally fall asleep. The 24/7 regimen is that of permanently open eyelids, in which we witness sleep degradation. Those who sleep in Torres' video did not just fall asleep, but they rather “shut down” like machines whose batteries have totally drained. In Dardot's drawings there are two central elements in his output: writing and time. The artist annotates phrases spoken in Zoom meetings and then shift them to drawings made on grid paper–an allusion of pixels. What draws one’s attention is the discrepancy between the maximization of time related to the practicality of Zoom and dilated, attentive temporality, which is necessary for the creation of these drawings. These establish some sort of meditative gesture, as if opposing to the dispersion caused by virtual interactions. In "I think I fell," Dardot visually translates the frequency of a shaky and distant voice narrating its connective fall.

This fall that seems an imminent condition of our present. Psychic collapses are all over the place. How to admit falls, vulnerability, in a world driven by performance, productivity, images reflecting success and well-being? Victor Mattina's painting "The court" (2022) alludes to the zombiefication of our existences, in which we continue to play normality amid a collapse. His feast of the dead alludes to this farce.

While Rafael Alonso's "Super fine work" (2022)evokes the glitch of an almost depleted monitor that has its normal operation interrupted, Érica Storer’s "Work with what you love, and then work your entire life" (2019/2022) presents a seriesof gifs showing scenes of fury in work environments. The precarious nature of the work and the various psychic disorders derived from it are here given a witty translation, as if we could still laugh among ruins.

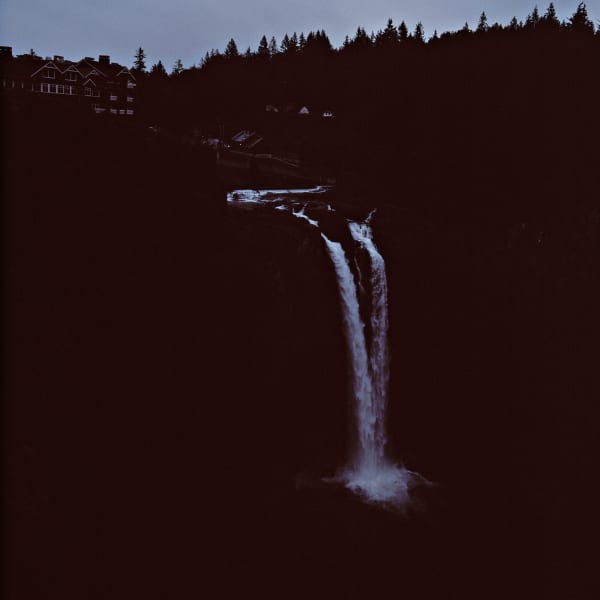

If we agree that one of the side effects of the 24/7 world and the inevitable algorithmization of our existence is the loss of a state of sharp attention to everything that surrounds us, and if we agree that the periods of solitude become scarce every day and that the dynamics of overexposed networks circles back to the incognito and unfathomable, then the works gathered here stress the chance of some attention, poetry and enigma left in this confusing conjuncture. Luiza Baldan's nocturnal waterfall emerges as pure mystery. Arorá's skittish and delicate drawings ask us to approach so that we can see its damp landscapes.

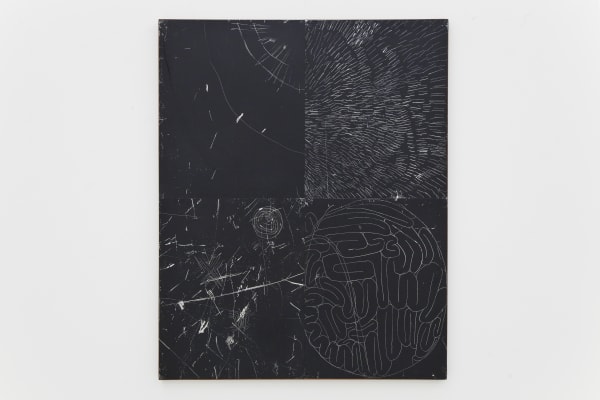

The rugged topology in Maria Laet's "Graphic bed" (2014), in turn, presents the artist's well-known poetic force–that of someone who knows how to write in a fine dialog with nature, disregarding the literalness of human language. A literal language, proper to the universe of information, which Cristiano Lenhardt conceals in his "Our voice". The objective functionality of journalistic writing is disregarded in favor of an organic calligraphy of shapes and colors that seem floating. Also floating are, extremely delicate and colorful dots that form a kind of suspended city in "Constructive (fabric)" (2021), by João Modé. “Spontaneous generation" (2022), by Daniel Frota, is also that sort of work that requires a careful look. Here, moths form a drawing in one of the corners of the gallery. "Moving drawing" (2021) subverts the iconography of the time count in favor of a poetic visuality that undoes the chronology of the clocks. As unidentified objects, all these works seek to establish other semantic systems to read the world.

Many of the works in this exhibition which depict brains in different presentations, media, and materials. Although unintentional, such occurrences somehow reveal an important aspect of the speculation we propose here. The signs of collapse come in different ways, while bodies get sick, exhaustion prevails, and cognitive chaos spreads evidently. When we reiterate the consequences of a time in which we live surrounded by screens, it is not a matter of thinking about screens, but rather what the interaction with them produces. There is no doubt that spending hours online is deeply changing our minds and that our subjectivities seem to mirror more and more the logic of algorithms. The presence of the works by Peter France, Mayana Redin and Frederico Filippi alludes–each in its own way–this universe.

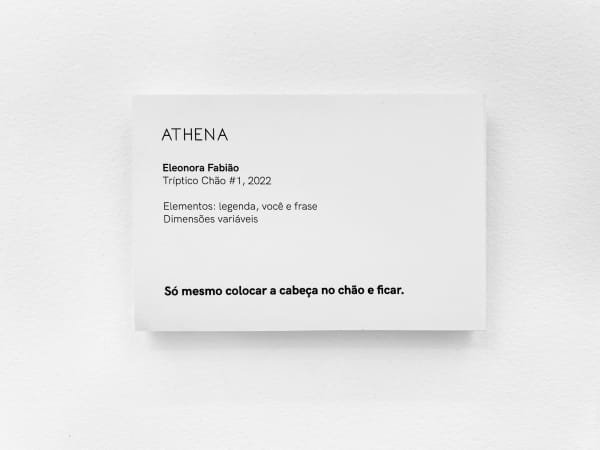

The state of cognitive chaos takes place in a context of dissociation from the body. We are witnessing the era of the “digital-zombie body”, in the words of Italian philosopher Franco "Bifo" Berardi. The work of Eleonora Fabião–which requires the audience to squat to be able to read, at different points of the gallery, the following sentences “just put your head on the ground and stay / just put your hands on the ground and stay / just your heart and stomach on the floor and stay”–relates to the antipodes of a current experience that represses the body and does not know any pause.

In the heart of the gallery is Jonas Arrabal's installation. It collects and reconfigures natural remains that, as amalgamated to elements such as iron and steel, remind us that the ocean of psychic collapse is also an artificial ocean. The intersection of nature and culture is the motto of "Human, inhuman, organic, and industrial" (2022). The encounter between machine, nature and language is also seen in Romain Dumesnil's "The unwritten script of an unspoken speech" (2015-2022). In "Arrangement (formation #3)" (2019), by Tadáskía, we see branches growing from the back of her head, as if it were possible to give another-more fertile and vital- destination to the seemingly disastrous paths of our time. Lais Myrrha's "Double exposition #11" (2022) undoes the typical objectivity of the photographic medium in favor of an overlay of images that causes Brasilia, a city whose image is solid in our memory, to gain other features. Do the organic forms and a sculpture by Maria Martins infiltrate as a foreign, unconscious body like unidentified object? – in the midst of the rational coldness of modern concrete.

"Slab #14 (Feed)", by Matheus Rocha Pitta, brings the word that defines the environments of social media above the orange image of the core of a black hole as captured by high technology. On this relationship that reflects on the perversion present in the dynamics of social media, the artist said: "There is a change now that is as terrible as a black hole: information is presented as a value as vital as food. It is no surprise that this same flow of information is called FEED, a feeding with neither pause or rest, where we are called (through the devices of freedom of expression and narcissism) to provide content to a machine, to feed a machine that corrupts any and all value that opposes to it."

The exhibition ends with a room dedicated to the work of Brígida Baltar, in which we see the projection of the video "No darkness". Over the course of ten minutes we stroll on a boat on the Sumida River in Tokyo. Under the dim light that signals the end of the day, the journey follows under a dark blue sky with the constant testimony of artificial lights that light up on the riverbanks. As a common feature of the artist's videos, there are no broad gestures here: just the dry record of the crossing with a still camera, a subtle soundtrack and the presence of a text that underpins the narrative: "(...) The lights begin to appear in the afternoon on river Sumida / soon the shadows will take diverse, undefined contours / and the scaring dark alleys and vulnerable streets / that shelter ghosts will disappear / no more gaps, no more invisible spaces / no more darkness / once I read that the sunrise and sunset / no longer orchestrate time in the city / without stimulus, melatonin now overflows into drugs / sleep postpones time / invents a break / noises get blurred / the muscles relax / and breathing is regular and slow / one does not think about the precise moment / when it magically lose senses / a bit later, some brightness makes us sleepless / (...) / but I would stay again on a full-moon night / looking at stars that no longer exist / or in a night forest / making the eyes get used to see / to the sound of the shrill symphony of insects / it is to Rudá that the Guarani sing at dusk / the lanterns, the lights, the fireworks / the poles and headlights in the city / numb us excessively / darkness is no more".

The Japanese capital is known for its intense artificial lighting, and it will be in a critical dialog with the meanings of this praise to continuous glare, which turns night into day, that the work will happen. Here, text and image have equal weight and importance. The journey through one of the many rivers that cross Tokyo witnesses simultaneously the end of the day and the beginning of another type of day, since the night never arrives. Little by little, on the poles, inside the buildings and on their facades, in the form of large-scale advertisements, dozens of points of light are lit to transform time into a large and never-ending amalgam.

What Baltar catches on her tour on the Sumida River is the assumption of a time that walks in the opposite direction of all that is put in her well-known moisture-related works – fog, sea air and dew. There we come up with misty atmospheres in which a slower temporality is suggested, requiring the audience to have a closer look. There, everything mumbles, instead of screaming. What is at stake there, and in Brígida Baltar’s work as a whole, is the praise of a world in which space is cultivated for unidentified objects.

Luisa Duarte and Victor Gorgulho

![João Modé, Construtivo [Paninho], para Ione, 2021](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/galeriaathena/images/view/8ea826fcaf39a85388cb564996c3e17ej/galeriaathena-jo-o-mod-construtivo-paninho-para-ione-2021.jpg)