With the air too heavy to breath: Group show

Galeria Athena is pleased to present the group show With the air too heavy to breath, curated by Lisette Lagnado.

André Griffo | Anna Bella Geiger | Antonio Dias | Antonio Manuel | Artur Barrio | Débora Bolsoni | Franz Weissmann | Frederico Filippi | Hélio Melo | Igor Vidor | Iole de Freitas | Iza Tarasewicz | Joana Cesar | Lais Myrrha | Laura Belém | Leonilson | Leticia Parente | Matheus Rocha Pitta | Raquel Versieux | Rodrigo Bivar | Rubens Gerchman | Vanderlei Lopes | Yuri Firmeza

What Now?

On the eve of presidential elections, the “human conviviality standards” of the “cordial man” find Brazilian society bisected by hate speech. Settled on the belief in a diverse tropical country, Sergio Buarque de Holanda’s post-colonial social theory of Brazil (1936) collapsed in the face of current rates of violence and homicide against young and poor (trans, black and indigenous) populations. Over six months have elapsed since the murders of Rio de Janeiro’s councillor Marielle Franco (PSOL-RJ) and driver Anderson Gomes with no indictments of those responsible for the crimes by justice.

It matters to know how this awareness translates into artistic language creation. In recent months, thematic exhibitions on the current democratic setback have multiplied, comparing present time to 1964’s military coup and its toughening after the enactment of AI-5, in 1968.

The show “Com o ar pesado demais pra respirar” (Air Too Heavy to Breathe) seeks to make a statement on the atmosphere of this comprehensive times of unique distress. With an invitation to show at a gallery which is opening a new venue at the south district of Rio de Janeiro (a state under federal intervention in public security since the beginning of the current year), I’ve asked each artist how the news have been reflecting on their daily lives, their mindset and their actions. I’ve received erratic reports, ranging from expression breakdown, to nihilism, and lack of concentration. After all, Athena Arte Contemporânea’s artists lived their age of majority while the country had a leftist government who has made poverty and hunger reduction their main agenda. What now?

The title of the exhibition was inspired by a work by Frederico Filippi, comprised of two galvanized steel sheets covered in black ink and other mixed media, such as oil, charcoal, spray paint, and pieces of paper covering scratched inscriptions. Given his background in aviation, the artist extracted from this repertoire the word “estol” (“stall”), which means the airplane’s loss of support, the moment when it “suffocates”. “It goes higher and higher until it can’t anymore, and then it begins to descend and involuntarily pitch down”, explain him. The work refers to residue from civilizations and it echos here as a pungent manifestation of the fire that has destroyed Museu Nacional da Quinta da Boa Vista (RJ).

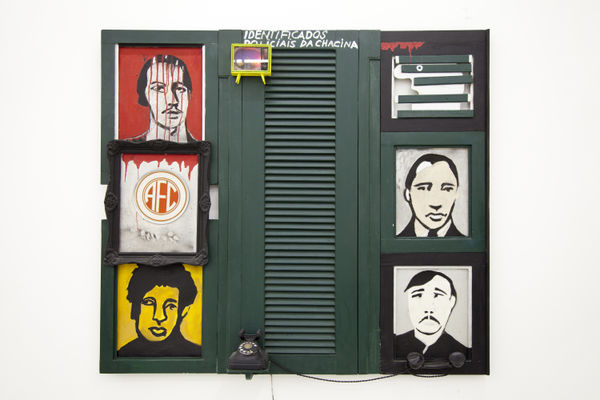

Image and headline manipulation has proved to be one of the most prominent practices to establish focal points with the 60’s and 70’s, and Rubens Gerchman’s pop figurativism shouldn’t stay out of it. In spite of the decades that separate it from Antonio Manuels’ Flans, the ideological content of print media is an irresistible material to artists who watched ex-president Lula’s arrest in real time. Supported by the painting practice, André Griffo witnesses the ubiquity of news in people’s daily lives, from television to newspapers. [The coup, the arrest and other conflicting tricks with democracy (2018)].

Volpi’s constructivity impregnates the imagination of artists who have trained their vision within folk festivities – to the point we may find methods of veiling in Lais Myrrha’s collages to resolve “background issues”. The word “background” refers both to composition and to politicians characters. Her collage series not only rewrites the political crisis faced by the country, suggesting a healing process [Damage Remediation], but also allow us to politicize Rodrigo Bivar’s aesthetic turnabout. For this artist, the crisis had reached a radical outcome when his paintings became abstract: “In 2016, figures vanished. There was no transition, it was abrupt. Painting white people on the beach seemed like a bourgeois hobby”.

Emblematic within the exhibition is one of Artur Barrio’s Bloody Bundles (1970), from the time he performed a public space situation in which he simulated bodies as thrown in vacant lots by the military dictatorship. There is a correlation there with Matheus Rocha Pitta’s series of photographs Brazil (2013), in which pieces of meat are combined with red soil from Brasilia, recovering the meaning of the word “brasil” (“brazier”) as “ember pit”. Pitta also shows images from the “Winners’ Gallery” series (2018), outcome of a cartography of survival gestures and of the work made from Machado de Assis’ saying, “To the victor, the potatoes“.

The story about the transferring of a million hectares from the Amazon to produce latex, much needed in the late 20’s by Henry Ford’s car industry, resulted in the artificial transplantation of a cookie-cutter American city to the Tapajós River’s margins. Yuri Firmeza’s current research about Fordlândia is shown next to a painting by Hélio Melo, self-taught, rubber tapper and activist who has engaged in exposing the dilapidation process of the forest’s natural resources. The native peoples issue is the subject of a video he made with Igor Vidor, Brô MC’s, name of the first native Brazilian rap group in Brazil (Aldeia Jaguapirú Bororó, Dourados, MS). This chants seek to publicize their struggles, mixing Portuguese and Guarani languages.

A cross-sectional line brings Vanderlei Lopes’ recent sculptures [(Trial and Error) Project], which allude to crumpled paper, closer to Leonilson’s geometric embroidery. One imparts value to the next. Neoconcretism keeps operating in contemporary production, but its references shifted meanings. As well as Vanderlei Lopes looked up to Leonilson, the latter, for instance, looked up to Franz Weissmann. It was important to bring here Weissman’s blows on plane from the Dented series (1967), to add a violence release to the sublimation tendency that defined the 90’s.

The third theme developed by the exhibition is the “experienced body”, which permeates both Raquel Versieux’s (with a comic/tense pun intended in “erosion/erection”) and Joana César works. In the latter’s practice the production has piled up inside a room and had to come out to the streets. In a way, mental disorders keep surrounding both her drawings made with hot air from a blow dryer pointed towards drops of ink that “are born from the belly”, and videographic self-portraits biting her nails to strip-off a feminine stereotype from herself. The visceral quality of subjective psychological processes is a known procedure in Anna Bella Geiger’s engravings from the late 60’s and in Letícia Parente’s brilliant video, Trademark (1975), in which the artist stitches the words “Made in Brazil” on the sole of her foot. A photo series (still pictures from a experimental film) by Iole de Freitas captures the light that penetrates the intimacy of the house, marking the transition from visceral body to a structuring body.

I would prefer not to, by Débora Bolsoni, explores a constructive path while bringing graphic content by Russian avant-garde, and reminds us that Herman Melville’s character (Bartleby) found no way out of his destiny but to remain incorruptible. The only non-Brazilian from the Athena group, Iza Tarasewicz was included in this event because she has been elaborating abstract sculptures from algorithmic combinations of chess moves. The strategic move that rules a war game engenders a networks of nodes which the artist recovers from artisanal practices of rug making.

Hovering over the gallery’s architecture (inside and outside areas), Laura Belém recovers the fiftieth anniversary of Sergio Bernardes’ film Desesperato (1968), which brought up the dilemmas of an intellectual divided between personal survival and decision making in the collective arena (guerrilla). His “Silent Film” sticker alludes to the film that was censored at the time, but also symbolizes the abandonment status of education and culture.

It’s thus apparent that political conflicts do not constitute explicit imperatives for all artists. The history of Brazilian artistic production under the parliamentary and media coup that orchestrated the deposition of President Dilma Rousseff is yet to be written. Beyond any empathy and solidarity with those who are disappearing, the description of the cultural institutions collapse serves as an allegory to portray the tragical lack of expectations the country needs to overturn. In this sense, a black canvas by recently deceased Antonio Dias, The Secret Life (1970), allows us to imagine the complexity of simultaneously being an artist and a political entity in turbulent times.

Lisette Lagnado