Permission to Speak

"Could this be just the natural order of things?" asked the old pig Major early on in his speech, which ended up serving as an incentive for Animal Farm. Published in 1945, the book[1] by George Orwell, recounts that one fine day, Mr. Jones’ farm animals realize that the worthless life they’re subjected to is not the natural order of things. Led by a group of pigs, they run the farmer off his property, deciding to build a place where everyone is equal. The seven commandments that would constitute the unalterable law by which the Animal Farm should govern its life after the revolution were gradually adapted, altered and excluded, until there was only one left: "All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others "— the original version, which read "All animals are equal," was changed in the middle of the night without anyone seeing.

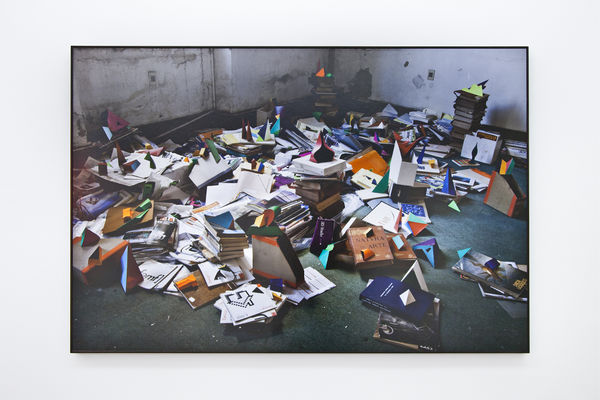

The exhibition Permission to Speak brings together artists whose works try to deal with this "natural order of things." What all the works have in common is that they bring references to discourse and history as constructions, taking special interest in the uses and variations of meanings that words can assume, depending on who is speaking, listening, or even when they are silenced. In the ambiguity hidden in the title, which points to an imposition (granting permission) and to a demand (requiring permission) at the same time, the exhibition reaffirms its interest in contemplating the place of speaking and listening. Here contemporary production is presented as a powerful tool for reassessing and rearticulating history, bringing to the present issues of the past whose impact can be felt today and in the future.

The story is recaptured in the works of Beto Shwafaty. In Anhanguera/Bandeirantes (2015), the artist proposes a relationship between the exploration missions to the interior of Brazil led by the bandeirantes (followers of the flag), and the economic development represented by the main access routes to the interior of the state of São Paulo, which give the work its name. In Abstrações Sujas (Dirty Abstractions) (2015), the main character is EDISE, the headquarters of Petrobrás, located in downtown Rio de Janeiro. Presented as a "symbol of so-called great Brazil" in the 1960s by the national press, decades later its image was circulated again in the media when the Federal Police began the first phase of the so-called "Operation Car Wash."

Other official national symbols are also present in the exhibition. In Jaime Lauriano's Bandeira Nacional (National Flag) (2015), he brings together a series of works which, through weaving techniques, seek to subvert the control and regulation of this symbol created as one of the transmitters of the feeling of national unity and sovereignty of Brazil, and a tool to bring the government and population together. This troubled relationship is also displayed in Vocês nunca terão direito sobre seus corpos (2015) (You will never have rights over your bodies), by the same artist. Institutional racism phrases, found in official communiqués and bulletins of occurrence of the Brazilian Military Police, gain body and presence when carved in wood. Another national symbol, our constitution, is the starting point of Reconstituição (Reconstitution) (2008). Here, Lais Myrrha selected all the pages of the Brazilian Constitution that have the word "exception." This word, which appears prominently in the reproductions made by the artist while the rest of the text is blurred, draws attention to the flexibility of reading the laws in the country and, as a consequence, the inequality in their applications. The works of Lais and Jaime make us think, from the silences they bring to light, that it is not only on Mr. Jones's farm that "some are more equal than others."

It is precisely because of the silence, or the impossibility/difficulty of communication, that other works take an interest, revealing how this is as important as speech in the construction of History and discourses. In Hoje tem cine (There’s Cinema Today)(2015), Laura Belém creates neon signs with titles from the films that marked the history of Cine Palladium, which was one of the most important movie theaters in Belo Horizonte. In the exhibition, there is the sign for Neville D'Almeida’s Jardim de Guerra (War Garden), one of the many films withdrawn and censored by the Military Dictatorship in 1968. Also taking an interest in the silent films that construct our h/History, the short subject Entretempos (Between Times)(2015) by Yuri Firmeza & Frederico Benevides comes from the archaeological material found in the port area ofRio de Janeiro—photographs, archive images, official documents and slave negotiations—to ponder the current process of gentrification that is spreading across the city today. But perhaps no silent film is more historically uncomfortable than the one revealed in Paula Scamparini's video-installation We-Tukano (2015). In one of the images we hear the Indian Carlos Doethiro Tukano, a political leader and tribal chief of the largest urban village in Brazil, Aldeia Maracanã, tell the story of his land to a group of children, in his mother tongue, while in the video next to it, which accompanies Doethiro's speech, white men of diverse origins seek to reproduce their words even without understanding their meaning.

Another group of works points to the exercise, collective and individual, of constructing meanings. In the photographic series O ensino das coisas (The Teaching of Things) (2015), Sara Ramos reveals how difficult it is to define certain concepts or words. The starting point are posters found by the artist in an abandoned design school in Uruguay, where students tried to express the content of words through forms. In EEDDM II - El encuentro de dos mundos (The Encounter of Two Worlds), created in 2013 by Vanderlei Lopes, the organic forms of the leaves, cast in bronze, have geometric and precise cuts made by the hand of man (cuts so precise that they are not found in nature). Here, the "two worlds" cited in the title can be read as nature and culture, and the attempt to build a (not necessarily friendly) relationship between them.

The exhibition is completed by Diego Bresani's photographic series. If much of the work gathered here is a departure from the thinking of elements of great History (without ignoring the certainty that it has an impact on individual life), Bresani's works show interest in the more personal dimension of this construction. His photographs, mostly in black and white and recorded on film, are similar to a kind of diary of the year that the artist lived in Paris. Observation of the world, its landscapes and characters, make up the essence of the work, which endeavors to reconstruct its own history and its relation to the practice of photography, after years of work in the studio, and with well-defined limits.

And so, Permissão para falar (Permission to Speak) makes us think that the world as we know it, either in its most personal or most public dimension, is a construction, an established and shared invention (peacefully or otherwise), and like everything invented, is invented by someone for a reason, often with a good dose of effort and "alternative facts," leaving other possibilities and versions aside. And being a construction, it could be undone and reinvented at any moment. All h/History is a matter of point of view. Or do you really think that this is the natural order of things?

Fernanda Lopes

![Vanderlei Lopes, EEDDM VI [El Encuentro de Dos Mundos], 2013](https://static-assets.artlogic.net/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/galeriaathena/images/view/3a758feb78dbb386b0f262f68744511ej/galeriaathena-vanderlei-lopes-eeddm-vi-el-encuentro-de-dos-mundos-2013.jpg)

![Vanderlei Lopes, EEDDM I [El Encuentro de Dos Mundos], 2013](https://static-assets.artlogic.net/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/galeriaathena/images/view/c8d132cf2bbf83009c3d67e5aee1b1d7j/galeriaathena-vanderlei-lopes-eeddm-i-el-encuentro-de-dos-mundos-2013.jpg)

![Vanderlei Lopes, EEDDM V [El Encuentro de Dos Mundos], 2013](https://static-assets.artlogic.net/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/galeriaathena/images/view/76dadad6f01309c9a19815a45741cdd3j/galeriaathena-vanderlei-lopes-eeddm-v-el-encuentro-de-dos-mundos-2013.jpg)